Hot take ratings on the Universities Accord

Initial impressions of the Universities Accord Final Report, a day after release

Hi everybody (somebody?) (anybody?)

This marks my first post on Substack under the banner of accessible quality. You might have read The Curios Case of Charles Dodwell and the Universities Accord also on Substack, written well ahead of the release of the Accord’s Final Report.

The views put forward in this piece are my own and are not representative of any organisation I may or may not be affiliated with!

There are already numerous pieces trying to defend, critique, or explain the Accord, and this ‘hot take’ is prepared to help me make sense of all 400+ pages, and in doing so, hope that it might be useful for others.

Before jumping in with my own views, this piece is probably a warm rather than a hot take. It is not deliberately provocative shallow commentary, but in writing a day after the report’s release, it is hard to be anything other than impressionistic.

To make it ‘cooler’, and deeper commentary, it is worth framing the report alongside some key public policy concepts relating to policy change.

The Accord Final Report seeks to catalyse a marked shift in post-compulsory education systems, and in doing so confronts a complex policy sub-system filled with very smart policy actors pursuing various shared, or mutually exclusive policy beliefs. This policy sub-system is comprised of various coalitions advocating for various policy objectives. This is the basis of the Advocacy Coalition Framework. Policy beliefs in this sub-system can be framed as:

core (ie - things that are unlikely to change, like one’s faith in god)

policy core (ie - also things that are deeply held, but policy specific like a strong commitment to access or quality in higher education, or both in my case)

secondary aspects (ie - getting into more technical elements of policy implementation like whether better resourced universities should make a contribution to an endowment fund that might benefit all tertiary institutions - more on that in a later post)

An initial take on the Accord Final Report can be viewed through the prism of it aligning with reasonably strong core, policy core, or secondary belief systems. This makes this a tepid to lukewarm take, rather than hot take, but with some provocative comments to keep it somewhat more interesting to write (and potentially read).

Report Structure

It would be hard to critique the structure of the report on secondary policy beliefs - although some might prefer a different font or referencing style, the report is pretty conventional and would appeal to those with strong policy beliefs on how a report of this kind should be framed. The only minor quibble I’d have is extent to which contributions are not cited specifically, and instead cited generically, but this is very minor.

Don’t be put off by the 400+ pages, a quarter of the report relates to appendices of who they spoke to, references etc. Don’t also take the lazy option of just reading the executive summary. The explanation in the full report is condensed in ways that are not always well represented in the executive summary. I personally have meandered from section to section, summary to detail, and detail to summary to get a clearer sense of where things might be heading and why. I’ll probably re-read and re-read.

The report steps readers through a series of chapters loosely focused on: 1. Context; 2. Skills needs (meaning some currently excluded will need to be included to satisfy needs); 3. Expanding opportunity (to fulfil skills needs); 4. Students (how much they should pay/repay, and be educated/supported); 5. Research; 6. System coordination and ‘stewardship’; 7. The Regions; 8. Funding; and 9. Implementation matters. Each of these chapters gets into details where divergent core policy beliefs and secondary policy belief systems will get into conflict across advocacy coalitions.

Chapter 1. Introduction and context ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Not much to see here other than saying this was a good process. Consultation was evident at every step of the way from Terms of Reference to Final Report, and there is evidence of reflexivity to the submissions received along the way. Hard for anyone to quibble with how the Review Panel went about the substantial challenges it faced. Also hard for anyone to get too excited about an introduction, however…

The introduction does include a new National Tertiary Education Objective. The objective resembles - in part or at least the sentiment of - The Best Chance For All. We do not currently have a tertiary education objective. The closest we have is the objects of the Higher Education Support Act. I documented the evolution of these objects in my doctorate which in short saw objects first introduced in a 1991 amendment to the Higher Education Funding Act - this was copied across into the Higher Eduction Support Act in 2003 (with the deletion of ‘more’ in purpose of ‘a more highly educated population’). The objects were expanded to include the specific contributions of universities in funding changes introduced in the mid-2000s, and further minor tweaks to support the Job Ready Graduates fixation on jobs and relevance to employers. Our national objective is therefore one that was drafted some 30 years ago, incrementally and opportunistically amended, and not one that seriously looked at the tertiary system as a whole. The proposed wording is good, timely, and well crafted, and sees this boring introduction elevated to 4 star status as a result.

Chapter 2. Meeting our current and future skills needs ⭐️⭐️⭐️

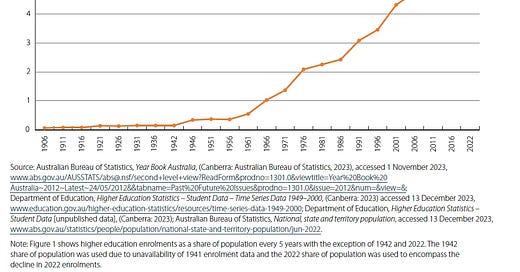

We already see some critique of long-terms projections for skills needs in the media (see editorial of The Australian 26th of February 2024). Whilst it is easy to critique economic analysis based on imperfect assumptions that generates precise numbers some 25 years into the future, one only has to look back in time to see how much higher education has grown. Figure 1 of the Final Report (screen grab below) shows just how sustained demand of higher education has been over the last century, hitting the first real decline in the period 2016 to 2022. It is impossible to extrapolate the trend line on forever, at some point you’d hit 100% of the population. The more important unknown, and subject to differences in core policy and secondary belief systems, is the point/s at which demand for skills is sustainably satisfied. For example, does the recent downturn in participation suggest we’ve hit peak demand, or is this result of policies and economic circumstances that have suppressed participation below the required level?

Martin Trow’s seminal work around the problems of expansion in higher education highlighted that once a higher education system hits a level of participation, growth in demand tends to be social rather than economic. More recently, and building on Trow, Simon Marginson highlighted that there are a multiplicity of factors that catalyse participation growth, operating in different ways in different jurisdictions and at different times (social, economic, policy driven etc).

My personal view is that the long-term trend towards higher participation will continue, and may more or less approximate that of the economic modellers, but the economic modelling should be treated as a best guess rather than precision science driving the reform process. This trend towards higher levels of participation will be expensive, and this is where we see much weeping and gnashing of teeth at who will foot the bill.

This chapter also gets into the weeds of policy detail, including skills passport and credit for prior learning. The later of which is an important mechanism for paying for the overall agenda. Current Higher Education Standards (Threshold Standards) make credit for prior learning conditional on not disadvantaging students by giving credit that compromises attainment of course learning outcomes. What the Standards don’t say is that students not be disadvantaged by having to pay for study covering learning outcomes they already have. There is a big opportunity here to make more efficient use of the participation that is funded by limiting duplication of learning through more liberal (and less stingy) application of credit for prior learning.

Chapter 3. Expanding opportunity to all ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Anyone that knows my work might be thinking I’d give this five stars, but I am taking it back a notch given the equity targets seem to misunderstand the underlying dynamics of the population reference values and higher education participation numbers. This is not just about a misrecognition of disability, and extends to other equity groups, and misses the opportunity to reframe the equity paradigm that was first introduced over 30 years ago.

There is much to commend with this chapter, with a commitment to enabling programs, which has been found to be an effective means of supporting access to higher education. Needs based funding, and mechanisms to address placement poverty are also welcome.

Reservations about expanding access have already been expressed in terms of the overall cost, and extent to which a growing share of the age cohort and by definition lower levels of school achievement can succeed in higher education.

Again these reservation can be viewed through the prism of policy beliefs. Is higher education only for the best and brightest, or a public good accessible to all? To what extend should the taxpayer pay extra to provide the teaching and support for students who are currently on the margins of successful completion.

The bigger picture historical view suggests that at various points across time, conceptions of who has a legitimate place in higher education sees fewer students taking a rightful place than what future growth in participation ultimately delivers. Participation today is six times higher than that of the 1960s, and with the right structures, policies, pedagogy and support, we’ll see that successful participation in future will be at a higher level than today. The challenge is to make changes to the system to accommodate growth rather than holding everything static and hoping students will succeed.

Chapter 4. Delivering for students ⭐️⭐️

This is a weaker chapter in my view, and addresses several distinct issues that who not hang together as well as might have been intended. Part of the chapter deals with what students pay, and the need to rejig the funding system to correct policy flaws introduced with the Jobs Ready Graduates Package. Other parts of the chapter deal with student safety, the student experience, and quality in teaching and learning. The chapter ends with a section on migration and international education.

The technical funding details and intricacies of HELP are what some policy wonks live eat and breathe, it’s their core, policy core, and secondary policy belief system rolled into one, and they’ll be happy to see a window opening to advocate for tweaks to funding clusters and rates, student contributions, and repayment mechanisms. This policy detail is important as the financing questions ultimately determine many of the other policy objectives and whether they can be funded. It is somewhat difficult however to transition from policy beliefs around the tax system to policy beliefs around student safety and the student experience, and the fundamentals of teaching quality. Let alone pivoting to soft diplomacy and international education.

I have read some stinging critique of how the report engages with teaching quality. My sense is that the panel might have recognised this is important, but felt that much of the detail could get passed onto proposals for a new Australian Tertiary Education Commission, or Centre for Excellence in Higher Education and Research. This critique will be important for policy reform implementation. If the advocacy coalition interested in teaching and learning feels their needs have been given insufficient attention, there is a risk that the broader agenda may confront push back that would have been readily avoided by a different structural and positional approach.

Chapter 5. Producing and using new knowledge ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

There is some pleasing policy commitment to better funding of research, but this will confront the macro questions of how this will be paid for in the budget. Expanding participation, providing better support, and better funding for research is a triple hit to the claims on the budget and it is unclear how this might be achieved given future budget demands associated with defence, aged care, disability, school and early childhood education, health etc etc.

One can see that the university research intensive advocacy coalition will be seeing this as the most important of all policy recommendations, no matter how strong their public positioning on ‘expanding accessibility to all’ or other policy objectives.

There is a bonus star awarded here for the report encouraging governments to lead by example and drawing upon university expertise (rather than spending more and more on consultants). I immediately read this as a direct response to issues highlighted by the PwC tax scandal.

Chapter 6. A dynamic, collaborative and responsive system that serves the national interest ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

This is my favourite chapter, combining my core, policy core and secondary policy beliefs in matters of policy and regulation. This calls out problems of policy making and implementation, and puts forward a new mechanism. I like it - and you should too.

A recommendation within this chapter is the establishment of a Centre of Excellence for Higher Education and Research. One immediately thinks of which institution or consortium might be best to host or manage a centre of this kind, and I can see problems with institutional settings that might be more ‘research’, ‘equity’, or ‘teaching’ focused. The trick here in my view is a Centre of Excellence that can balanced these policy beliefs and institutional orientations. I hope they choose well.

Chapter 7. Serving the regions through tertiary education ⭐️⭐️

Not much to see here - more of the same in my view. Will be well received by the regional advocacy coalition, but I don’t see this will be front and centre of peoples minds across other advocacy groups.

Chapter 8. A new funding model to underpin growth and quality ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

I recall many years ago , a Vice-Chancellor, Glyn Davis making comment about the challenges of meeting load targets given penalties for under or over enrolling under a former funding regime. He was quoting someone else that this was akin to “landing a jumbo jet on a ten cent piece”.

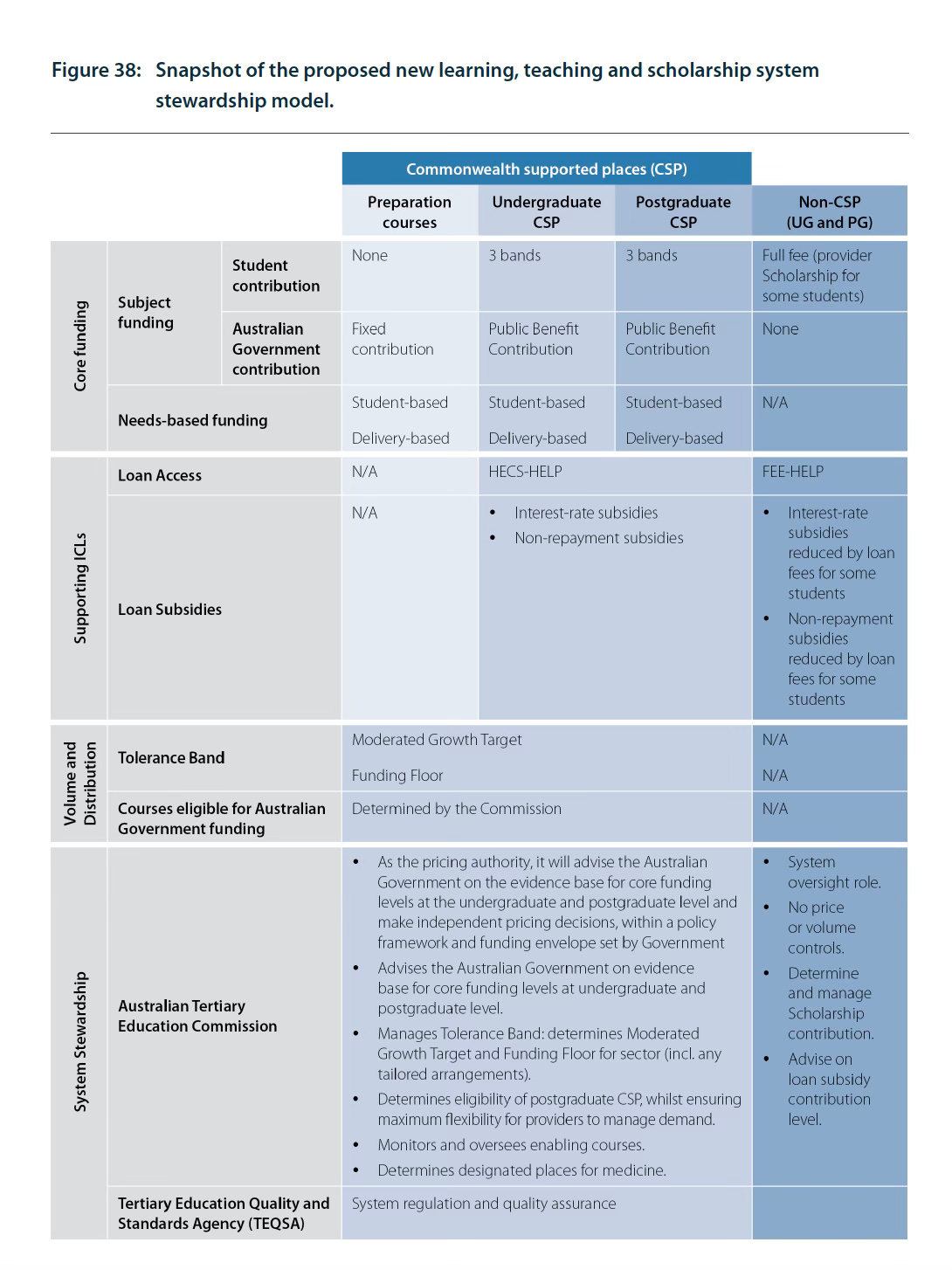

The proposed funding model (see screen grab below) opens lots of questions around balancing enrolments across preparation, ugrad and postgrad load across subsidised and full fee places, and between funding floors and moderated growth targets, whilst satisfying equity targets and completion bonuses. To me this will put huge demands on load planners who’ll be asked to land an airbus A380 on a twenty cent piece.

The overall framework does, in my opinion, provide a workable framework moving forward that will moderate the excesses of the blank cheque of demand driven funding, and still provide a pathway forward to growth that doesn’t merely lock in the relative size and scale of existing institutions. This view assumes that technical detail of funding rates will be sound, and governance through a new Australian Tertiary Education Committee will be strong - but if one’s core belief system tends to optimism this is a valid assumption.

The biggest issue I see with the proposed model is that there is an unspecified commitment to the role of full fee provision in undergraduate and postgraduate education. Given the issues with full fees in the past (think campaigns against $100,000 degrees in 2014, and removal of full fees when Kevin Rudd came to power post Kevin-07), this may well be an area where advocacy coalitions mobilise to push back strongly if full fees are permissible in some programs in some public universities.

Chapter 9. In closing ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Hard to get too worked up about a conclusion - but its an opportunity to think about the package as a whole, and how implementation is framed. Different groups, with different belief systems will rank all or some parts off the report between 1 and 5 stars. My view overall assessment is that the Panel have done incredible work, in a highly consultive manner, and put forward a road map for reform that is far from perfect, but one that all stakeholders should be prepared to get behind. We might see through a new Australian Tertiary Education Commission, better ways of fine tuning proposals, building consensus, and mediating compromise that will bring all the 1 star ratings to a workable 3 or 4 star rating and get our vitally important tertiary education systems fit for purpose for the next decade and beyond.

Has this been useful?

If you found this useful - please comment / share or reach out via socials:

Twitter/X @MattBrettLTU BlueSky @mattbrettltu.bsky.social

This is such an informative and engaging piece. It is so handy for me as an educator as it summarises the Universities Accord Report and also provides lively commentary. I love the star ratings!!! And my favourite line: "and this is where we see much weeping and gnashing of teeth at who will foot the bill." So true!! I'll be reading everything on this substack! love it!